Patrick Gaines

What exactly stands in the way of organizational leaders in fundraising?

How can development leads unlock new possibilities for their higher-ups?

Whether it be time on hand, a leader’s perspective of what will be asked of them in fundraising, or good old-fashioned fear – we urge development leads to work with leadership to address the resources needed to approach (and pass!) these hurdles effectively.Making Time…

One of the most significant and most complex barriers to an organizational leader’s fundraising success is time. Whether you are the dean of a college, the president of an organization, or the CEO or executive director of a nonprofit, your management and governance duties, along with obligations to boards and committees, take a significant amount of time and energy. While leaders typically delegate much of their day-to-day tasks, they must oversee many additional projects. A productive way for leaders to make time for fundraising is to integrate this work into their other duties. Development is not isolated to its own task but rather a daily practice when done well. This means that when leaders present their organization’s vision to their board and staff, they remind them about their role in the philanthropic ecosystem you continually build together. This expands the amount of time and energy leaders put toward fundraising and will bear fruit when they can dedicate time to making an ask, thanking a donor, or doing discovery or qualification visits.The phrase “When do I have time to fundraise?” inevitably arises, especially when the chief development officer relays that building relationships takes multiple touchpoints over years.

Creating time to fundraise is linked to effective budgeting – leaders and development leads should work together to understand what additional resources are needed to prime their team for success. Consider people, tools, processes, and associated costs – ask if your investment in each is worth what you are receiving in return. Recognize that just like for-profit businesses, marketing, PR, and communications are essential to fostering general awareness of what your organization does, which primes your donors and prospects for deep and meaningful engagement.

Defining Responsibilities

Lack of clarity around a leader’s role in development and what activities are needed for them to fulfill that role are significant barriers to their fundraising success. When a chief development officer says to their CEO, “You are the number one fundraiser for our organization,” they should also provide them with actionable work to live up to this position.

To be the number one fundraiser for their organization, leaders should take responsibility for setting the tone for a rich, positive culture of philanthropy. This should be top of mind, along with setting the mission and vision of the organization. Leaders should unapologetically champion philanthropy at staff and board meetings, events, and public relations opportunities. Development heads can remind their leaders of this and ask them to introduce themselves at events by describing why philanthropy is essential to their work. Lead fundraisers should emphasize to their higher-ups the importance of embracing and embodying this role to drive everyone in their organization to understand their role in elevating a positive culture of philanthropy.

Nonprofits intentionally establish themselves as tax-free organizations with the knowledge that they will ask the public for support. Leaders can weave this understanding into organizational storytelling to assist in building a positive culture of philanthropy. Individuals, consciously or unconsciously, look to leaders to know how they can contribute to the mission and vision of an organization – and leaders should consistently and earnestly invite others to contribute to the work being done. Explicitly stating, “We are providing a public benefit, and we need the public to support that benefit,” clarifies expectations and needs.

Development heads should also work with their higher-up to be specific about the number of people or percentage of the organization’s overall donor pool in the leader’s portfolio. To some degree, leaders should focus on larger fundraising opportunities, though relationships should be the deciding factor when determining who the organizational leader is responsible for cultivating. A leader’s responsibility need not hinge on bringing in a certain amount of revenue, as they may be able to foster a fruitful relationship with a few mid-level donors who could make transformational gifts down the road. Depending on your organization’s size, the leader’s portfolio could be anywhere from 15 to 25 individuals, with the development lead supporting a pipeline of new donors and prospects flowing in.

Know Thyself

Leaders should define their fears in fundraising and work with their development leads to understand how they can effectively navigate them together. CEOs take this approach with other areas, such as human resources (by hiring incredible talent acquisition staff to advise on hiring), and fundraising should be no exception.

It is perfectly acceptable to be an organizational leader who prefers not to make a fundraising ask directly. Instead of forcing this work upon the CEO, we recommend a team approach where whoever is most comfortable making the ask does so – likely the staff or volunteer with the best relationship with a donor or prospect. When everyone involved in fundraising knows the role they thrive in, they can build upon these strengths. For example, perhaps you are a leader who can eloquently speak to what makes your organization’s impact unique in your community and world – a valuable asset when building and deepening connections with donors. Leaders can also engage in stewardship and even some discovery work as training and a way to keep the pipeline moving.

No matter who is directly asking for a gift, fear of the word “no” should be investigated.

A leader’s portfolio will hold only those already committed to their organization – no blind or first dates. These donors have an established emotional connection with the organization’s mission, as well as the passion and ability to step up in a bigger way. They’re members of the inside circle – connections with them will be warm and primed by their desire to see your organization succeed.

While some nervousness is expected (I can say from many years as a musician that a bit of stage fright is normal and needed), everyone on the donor relations team should be prepared enough for an in-person ask that they are not fearful of a possible “no.” Roleplaying cannot be underestimated as a way to get comfortable with in-person asks. Again, musicians practice their work over and over before sharing it with the world – and those on the ask team should rehearse their performance as much as needed to approach their donors with confidence. Leaders should ask themselves what they are terrified of and practice navigating that response from a donor when absolutely nothing is at stake. Non-apologetic replies to a “no” along the lines of “thank you for letting me know, that is why they are here,” can move your conversation toward closing a different kind of gift.

Development Leads Can Increase the Confidence of Their Leaders

Statements like “I have confidence in you” remind leaders why they are in their positions. Telling leaders that you see how much they take on (including criticism) and that others have a great deal of trust in them will elevate their readiness to navigate in-person asks with greater comfort.

Alongside the fear of “no” is the misconception that asking for a gift is asking someone to make a sacrifice.

Development leads should coach their leaders to understand that major gift asks are directed at those who play the role of family and close friends.

We have a responsibility to those who care about an organization’s future and to inform them when there is an excellent opportunity to enhance the extraordinary work being done. These conversations often include points like, “We know you believe in us, we are grateful for your commitments so far, and we ask you to lean in again or further or toward something new.” A “no” in these conversations helps get your team closer to knowing the next steps in reaching your development goals.

When we do hear “no,” it is not toward leadership or the organization – but toward the time, amount, or project.

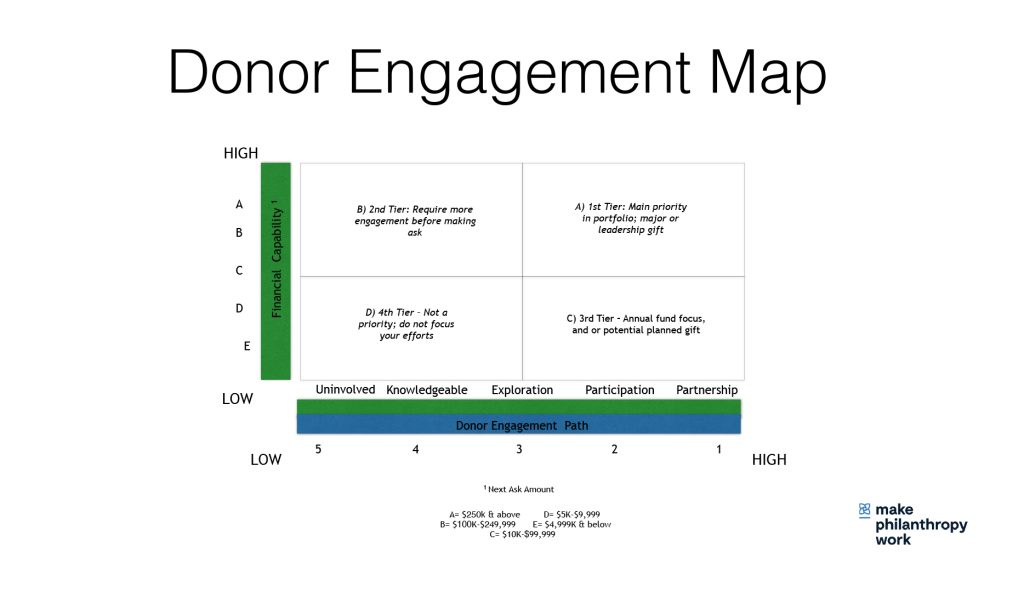

A great tool for establishing the appropriate ask amount is our Donor Engagement Map below, which qualifies prospects and donors based on their affinity and capacity to give. However, often a pivot might need to be made toward an alternative ask, and a development lead can help navigate this either in the moment of a face-to-face meeting or over a period of time. Again, the Donor Engagement Map comes in handy in adjusting the next steps with particular donors.